She’s alive! She’s ALIIIIIIVE.

(If only I made my return to the blog two weeks ago, this GIF would have been more appropriate. Oh well.)

I am back after a long, long, long hiatus with a new review of a much anticipated read: Margaret Atwood’s THE TESTAMENTS. This one is going to be a bit lengthy, so buckle up, friends!

**Spoiler warning for TESTAMENTS and its prequel, THE HANDMAID’S TALE.**

THE TESTAMENTS by Margaret Atwood

RATING: ★★★★

GENRE: Dystopian

THEMES: Reproductive rights, personal freedom, gender equality, radical religion.

TRIGGER WARNINGS: Suicide, violence, sexual assault, self-harm.

Admittedly, I came into THE TESTAMENTS with some reservations, mainly surrounding the fact that it is a sequel written 25 years after its predecessor, THE HANDMAID’S TALE, which carries its own cultural weight now, arguably, more than ever–protests against Trump’s administration often feature women in Handmaid uniforms, the Hulu show that has reinvigorated the interest in the original novel and has been so successful that it is now continuing past the book’s plot. I worried that THE TESTAMENTS was Atwood’s surrender to fan service in the midst of the show, but I will be the first person to admit that I was wrong.

THE TESTAMENTS is not a direct sequel to THE HANDMAID’S TALE. Where HANDMAID ends with protagonist Offred’s future dangling on the last page, THE TESTAMENTS only contributes to the mysterious, up-for-reader-interpretation ending by abandoning Offred as a narrator and instead focusing on three voices to color the Gilead that readers have been acquainted with: Aunt Lydia, one of the founding figures of the dystopian society; Agnes, a Gileadean girl who soon finds out that she is the daughter of a runaway Handmaid; and Daisy, a Canadian girl whose world is violently changed when her parents are killed in a car bombing. A major strength of THE TESTAMENTS is this split narrative, which allows for a more complex and well-rounded view of the world than the singularly-narrated prequel. I appreciated that the mystery that I was left with at the end of the first novel was not directly solved. Had it been neatly packaged up in its sequel, I may have lost interest. It seems anti-Atwood to package everything up in a pretty bow and give clear solutions.

The split narrative also gives the reader three truly intriguing stories, the most Atwood-ian of them being Aunt Lydia’s. A judge on the onset of Gilead’s terrorist coup against the United States, Lydia is forced to not only abandon the rights she has worked to the bone for, but to make the decision to embrace the new regime or die. Lydia chooses the former, transforming into a cool and calculated figure that would continue on to forming the very tenants of Gilead’s educational system for women that formed them into Wives, Handmaids, Aunts, or Marthas. To prove herself as an Aunt, Lydia is tasked with executing a non-conforming woman in front of an arena full of imprisoned women (at the end of a chapter that reads not unlike the horror stories of border camps in the US where immigrants are being detained in heinous conditions). Knowing full well that this will test her moral integrity, Lydia shoots the woman kneeling in front of her anyway, prioritizing her success and survival in Gilead’s top tier:

This was Commander Judd’s test: fail it, and your commitment to the one true way would be voided. Pass it, and blood was on your hands. As someone once said, We must all hang together or we will hang separately.

One of the targets was Anita [Lydia’s former co-worker]. Why had she been singled out to die? . . . Perhaps it was very simple: she was not considered useful to the regime, whereas I was.

Lydia does regret this decision, and is repulsed by it, but concedes that it’s necessary. Her complexity is what makes her narrative so intriguing: it is a true show of what one must sacrifice in order to survive in a cruel world.

Ultimately, Lydia’s conformity is only a display, as she has been working behind the scenes with the Gileadean liberation group Mayday to tear down the very people and society that has elevated her, submitting intel and kompromat (thank you, Ian, for this term!) of the abuses and corruption that the male founders of Gilead commit on a daily basis via microdot technology. This plot line was easily the strongest of the three, and had echoes of the current whistleblower testimonies in the United States and White House leaks, following the theme that despotic governments can be torn down from within.

TESTAMENTS is not undeserving of criticism, however. While the split narrative structure is well-rounded and fascinating in new ways than HANDMAID offered, it has its weak spot in Daisy’s plot. A Canadian girl, Daisy is raised with virtually none of the oppressive restrictions placed on Gileadean girls like Agnes. A regular glimpse of life across the border comes regularly in the form of the Pearl Girls, missionaries sent to Canada and abroad to convert new Handmaids, Wives, and Aunts to bring back to Gilead. Daisy’s parents, running a thrift boutique in Toronto, appear to be entertaining the Pearl Girls who come to visit, accepting their brochures and generally being kind to the young women.

When her parents’ car is destroyed in a bombing, killing both of her parents, Daisy learns that her parents are Mayday agents collecting reconnaissance from Gilead through the Pearl Girls brochures. As if this is not a staggering reality in and of itself, Daisy also learns that she is actually a fugitive from Gilead: the famed Baby Nicole, an infant who was taken from the country by Mayday forces and a symbol of scorned virtue. Gilead has been looking for Daisy for years, and she now must use her identity to get one last piece of incriminating evidence from Aunt Lydia.

Daisy is crass, blunt, and stubborn, but ready to accept the task, trained in martial arts and Gileadean customs by Mayday in the hasty days before she is to be sent on her mission. Daisy becomes nearly insufferable at this point: despite the very present dangers that she faces if she does not conform to certain societal constructs for women–like not cursing, speaking politely, and generally being submissive to authority–she adamantly continues to act in a way that would deem her nonconforming. This is something that should have had an actual impact on the narrative because we have been told that it would, but instead her behavior is dismissed by those around her as a symptom of her “sinful” Canadian upbringing. Juxtaposed against the very dire consequences of nonconformity in Aunt Lydia and Offred’s respective narratives, this feels inauthentic: Daisy has a shining set of plot armor that allows her to glide past the strict rules that had women executed by gunshot mere chapters earlier and hanged on the Wall in this narrative’s prequel.

A lack of risk, especially when the intrigue of Offred and Lydia’s narratives is based on the risk of being discovered and killed, is what ultimately makes Daisy’s plot fall incredibly flat.

There are also some predictable elements in Agnes and Daisy’s plots that are pretty easily discovered at a first glance: when both girls are revealed to not be the biological children of their parents, a thread between them can be easily drawn. Agnes’ childhood memories of being run through a wood by a woman and ultimately recovered by who she assumes to be her biological mother is assumedly a sly reference to Offred’s escape to Canada. Likewise, Daisy’s fixation on Baby Nicole before learning of her true identity is a heavy handed toss to the reader, an element that, again, feels very anti-Atwood.

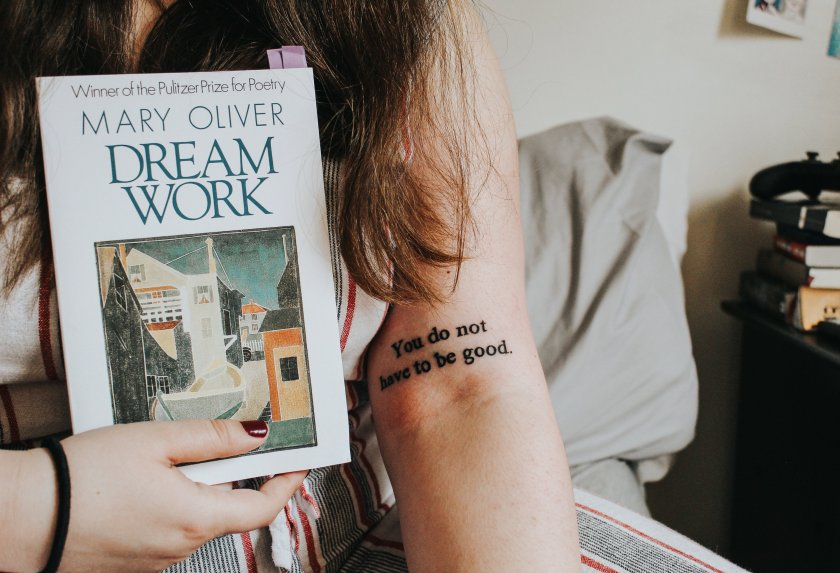

THE TESTAMENTS’ chapters are split into titles implying testimonies and documents in what I initially assumed would result in a court case or arrest, but ultimately results in a historical forum set after the fall of Gilead. After the blackmail delivery cache embedded into a tattoo on Daisy’s arm–a genius tactic–is delivered to Mayday, there is an unsatisfying leap to a conference set in Maine after the United States has been rebuilt, with women academics and studies on the totalitarian regime.

While the historical view offered a clean way to tie up the end of the three plot lines, it was wholly blasé to read when the lead-up to the end of the novel left me expecting a glimpse into a dramatic, epic, Earth-shattering toppling of Commander Judd and the founding fathers of Gilead. Instead, readers were left with a cold synopsis that had no sense of time or pacing: how long after the fall of Gilead did the symposium occur? When did society begin granting women the rights they had eras earlier? On that note, when did the events of the narrative take place? Atwood has a flair for mystery, yes, but these questions seem more like plot holes than details that can be left to a readers’ interpretation.

I appreciate that THE TESTAMENTS is a standalone book from THE HANDMAID’S TALE. It certainly reads like a cousin to the gargantuan classic: where HANDMAID’S is a bleak political horror and cautionary tale, THE TESTAMENTS is a brighter, espionage-riddled science fiction dystopian that reads closer to THE HUNGER GAMES or other similarly-successful YA dystopians (which is no insult!).

I’ve said in my review of VOX by Christina Dalcher, another tale of women losing their rights to a misogynistic government, that HANDMAID played on the fears of contemporary women readers in the 80s, and that’s what makes some of the elements of the classic novel feel a bit farther away from a 2019 reader. THE TESTAMENTS has clearly caught up to some sentiments amongst the current administration in the United States, the most salient of them being the importance of making corruption and other morally wrong doings of political figures visible. While we wait for the whistleblower testimony to unravel and impeachment proceedings to begin, THE TESTAMENTS offers a hopeful glance of what’s possible when brave people raise their voices.